Twenty years ago today, my friend Alex woke me with a phone call. I was a 20-year-old undergrad in Halifax, Nova Scotia — one hour ahead of New York time — and it was close to 10 a.m. A plane just hit the World Trade Center, Alex said. Had I heard from my family in New York City?

Few of us had cell phones back then, and my Uncle Robert was one of them. When I tried to call him and it went straight to voicemail, the reality of the situation started to sink in. I called my Uncle Greg, the other hot shot with a cell. Rob was in the towers, he said. It was Tuesday morning — where else would he be?

Like many who lived through that day, my life is pre- and post-911. Before 9-11, to me, the World Trade Center was a fancy office building, one where my uncle Robert happened to work, not a tourist destination or a symbol of American prosperity. It stood out among the city’s Beaux Arts landscape as a sleek, futuristic beacon, and I jumped at any excuse to visit. I recall the thrill of procuring a visitor sticker with my name spelled correctly at the north tower security desk. I remembering wandering through the maze of elevator banks until I found the one bound for the uppermost floors, where Uncle Robert worked in the offices of Cantor Fitzgerald. Rocketing up elevators is how I learned to pop my ears as a child, and no elevator in Manhattan was faster than those in the World Trade Center. I remember looking out the window of my uncle’s office into the endless horizon of buildings and thinking how lucky I was to call this dense island home, as if all the buildings and sidewalks belonged to me.

Back then, pre-911, that was how it felt to grow up in New York, as if the city was ours alone. No one ever wanted to visit. In movies and television shows, New York City was dangerous, dirty and expensive, but also flashy, fun and exciting. To those of us who lived there, the city was all of those things. We accepted the good and the bad with a blithe ease. Uncle Robert survived the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, but I honestly don’t recall the adults in my family talking about it, at least not with us kids. Nor when when my aunt unwittingly dodged a mass shooting on the Long Island Railroad by taking a different train, or when an armed robber surprised my mother and siblings in our apartment. New Yorkers are survivors who are defined by trauma and resilience. Before 9-11, it was a solitary honor. I repeat, nary a cousin, camp friend or penpal ever wanted to visit. According to the adults, sports meetups and academic competitions were always in Queens or New Jersey because parking and hotels were too expensive in the city. But we knew it was just that no one else had lived enough to be tough like us. When I recently visited the city for work, a colleague remarked that she thought I was from upstate. It pierced like the harshest of insults. I may no longer live there, but I am always a New Yorker. I’ve earned the title.

After 9-11, the world shared in our trauma and mourned with us. Our grief was collective, a national day of remembrance, a turning point in history. For a brief moment in time, Rudy Giuliani emerged as America’s mayor, a respectable leader. The story of my uncle’s life and death became part of a bigger narrative that continues to evolve. It felt weird, especially as the terror attacks became the justification for war, the demonization of Islam and the transformation of our national security agenda. I still struggle with how to privately grieve the public loss of my uncle given what his death has spawned. I still struggle with how to talk about it with my family.

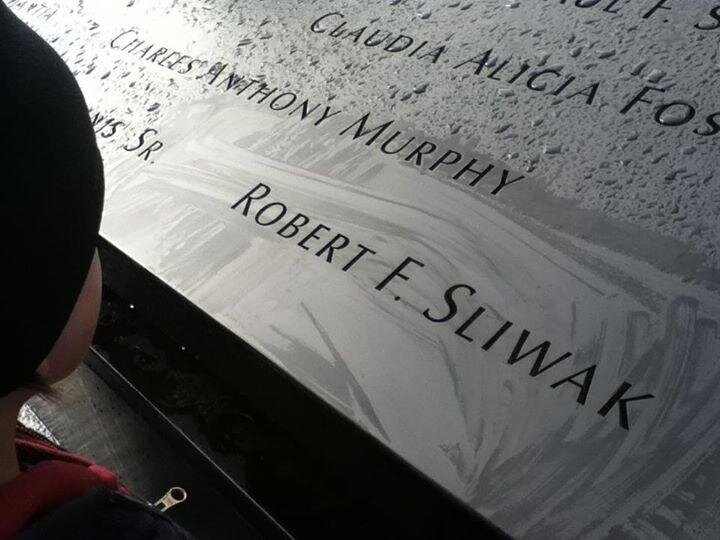

About three weeks after 9-11, I returned to New York for my uncle’s memorial service. His remains had not been recovered, but the time had come to acknowledge the loss of Robert Francis Sliwak, a beloved husband, father, brother and uncle. Getting there was no easy feat with commercial flights into New York grounded, and my school community pitched in. My friend Matt drove me to the port of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and the dean of students paid for my ferry ticket to Maine and my bus ride to New York. To this day, I hear from my Canadian friends more than anyone else on each anniversary, and remain grateful for their fellowship.

The towers were still smoldering when I arrived in New York, blanketing downtown in a dark plume of smoke that was visible from our rooftop in Yorkville. As the writer in the family who had eulogized my father three years earlier, I volunteered to do the same for Uncle Robert. At his standing room service in Long Island, I recalled my visits to his office and his visits to our apartment to raid our fridge. I described how losing him felt like losing another father, since he was among those who stepped up to help my family after my father died. I pleaded with the crowd to stand by my aunt Susan and my cousins. Ryan was just 6, Nicole and Kyle just 3 when their father died. Now, looking back over the past 20 years, I fear that I failed to heed my own advice. I left New York in 2008 for a change of scenery, to escape the ghosts, and we drifted apart. Through social media, I’ve caught glimpses of their inner lives and how Uncle Robert’s death continues to shape their identity.

“The hardest part about not growing up with my father was not being able to remember the person he was,” my cousin Kyle, now a 21-year-old recent college graduate, said in an Instagram tribute. “My story is still being written and my connection to him has only grown ever since his passing. So on this day, I do not mourn his loss, but celebrate his life.”

Today, my mother absurdly called me around 7:45 a.m. Why? To see how I’m doing, she insisted, after I told her I wasn’t feeling well the day before. I couldn’t help suspecting she did it to rouse me for the ceremony, just as she still calls to remind me of birthdays, wedding anniversaries and (increasingly) deathaversaries. Anyway, it worked. Today, for the first time I can remember, I tuned into the ceremony at the 9/11 memorial. The tolling of the bells marking each deadly moment sent chills throughout my body. Then, the reading of names began. There’s no way I’ll make it to Sliwak, I thought to myself. Suddenly, I recalled my first trip to the 9/11 Memorial and Museum. For years, I avoided it. Finally, I went for the first time in 2016 at my husband’s request. As morbid as it may sound, it felt like a homecoming. There’s a priority line at the museum for relatives of people who died in the attacks who can enter for free. New Yorkers love preferential treatment since so little of the city is just for us.

The real perk is access to the repository of the city medical examiner’s office, a secure room within the museum where unclaimed and unidentified remains are stored. It’s one of few places that is still ours, where we can be alone with our grief. I don’t know this for a fact, but it stands to reason that Uncle Robert is in there, somewhere. I look forward to returning one day.